On the way into the city of Gdańsk, Poland, my taxi passed a few cars with Ukrainian license plates. The driver told me 2½ million refugees from Ukraine have crossed the three-hundred-mile border.

Since the invasion began, Poland has welcomed more refugees than any other European country. Poles have provided food, shelter, health care, and even jobs to their besieged neighbors. Poland is a leading contributor of military aid to Ukraine.

The citizens of the two countries share a mutual concern about the imperialistic fixation of Putin’s Russia.

In my hotel lobby were a row of clocks on the wall indicating the current time in major cities of the world, including New York, London, and Beijing. A Ukrainian flag covered the Moscow clock.

Frequently, Gdańsk has been at the forefront of earthshaking events. In 1939 the city was the scene of the first battle of World War II. In 1989 a Gdańsk-based labor union ended communist-party rule in Poland, an event that influenced the eventual breakup of the Soviet Union.

And now, in the 2020s, Poland is leading the European response to the Russo-Ukrainian War. Touring Poland during the invasion, according to my guide, “gives a big middle finger to Putin.”

Shape shifting

Throughout history, Poland has been a Cheshire Cat of a country, periodically appearing and disappearing, sometimes whole and sometimes in parts.

In 1619 the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania, at over four hundred thousand square miles, was the largest country in Europe.

After losing a war to Russia in 1772, Poland was forced to give up thirty percent of its territory. In 1793 Russia and Prussia (now northern Germany) felt threatened by an invigorated Poland, so they helped themselves to more slices.

The Poles fought back to no avail. In 1795 Russia, Prussia, and Austria divvied up the leftovers and in the process wiped Poland completely off the map.

After Napoléon’s defeat in 1815, the country of Poland was reinstated, but over the years lost chunks of its territory to both Russia and Austria. The country regained its status as an independent republic in 1918 after World War I.

Then, forty years later, Nazi Germany barged in.

Ground zero

In 1939 Germany and the Soviet Union made a secret pact. The two powers agreed to invade Poland simultaneously, chop it in half, and exterminate its citizens.

On September 1 Nazi Germany attacked Westerplatte, a military garrison in the harbor of Gdańsk. The attack marked the start of Germany’s military aggression and kicked off World War II.

The Nazis anticipated a quick victory. Instead, two hundred Poles repelled thirteen assaults by three thousand Germans over seven days.

In the end, the Poles surrendered, but the defense of Westerplatte remains an inspiration to the nation.

Going postal

I visited a small post office, an improbable beachhead for the Nazis. When they began their assault, the office was targeted because of its telegraph office. Anticipating a possible attack, the Poles stacked weapons in the building and trained the postal employees as military reservists.

Over fifty of them defended the post office. On the same day as the Westerplatte offensive, the German SS attacked the building. Two breaches were successfully repelled before the Nazis resorted to flamethrowers.

After a seventeen-hour battle, thirty-eight surviving postmen surrendered. They were incarcerated, tortured, court-martialed, and executed. The Nazis refused to treat them as POWs.

For fifty-two years their place of burial remained a mystery. In 1991 construction workers found their remains in a mass grave.

Today the building is a museum that honors the civilians who defended it. It still operates as a post office.

Grass and gold

Poland is the size of New Mexico with thirty-nine million inhabitants, making it the fifth largest country in the EU. The Poles, descendants of West Slavs, occupy the tribe’s original homeland along the 650-mile Vistula River, which empties into the Baltic Sea.

To more easily navigate Poland and the Polish language with its hissing sh and ch sounds, I joined a tour.

Several in the group have Polish last names and family roots, including one tour member related to Vic Janowicz, winner of the 1950 Heisman Trophy.

Nine million people in the United States self-identify as Polish-Americans. Chicago has the largest population of Poles in the world outside of Poland. So many Poles have emigrated to Chicago, the city is jokingly referred to as the capital of Poland.

Our guide was Gdańsk native Agnieszka (Agnes, for short). Her ringtone is “I Feel Good” by James Brown.

After introductions, we walked along the river to dinner at a café, where we toasted the start of the tour with wódka (vodka). Although Russia and Sweden developed their own varieties, the first recorded reference to vodka was in 1405 in Poland. Historically, the beverage is made from potatoes and grain.

Later in the tour I had opportunities to sample a couple of traditional vodkas. Żubrówka Bison Grass, first distilled in the 1500s, contains a handpicked blade of sweet grass in every bottle.

Perhaps the more interesting ingredient, however, is precious metal. Small flakes of twenty-three-karat gold are suspended in Goldwasser, a vodka first produced in the 1600s. After a shot of the glitter, I felt of greater value.

Market town

Gdańsk is a city of a half-million on the coast of the Baltic Sea in the north of Poland. It has been an important trading port and shipbuilding center for centuries.

In 1361 the city joined the Hanseatic League, a network of merchants and towns that dominated sea commerce in northern Europe for five hundred years. Members set up trading centers, built ships and docks, and organized armies to protect their business from pirates. Sort of an early version of the European Union.

I toured Artus Court, the clubhouse of the city’s Hanseatic members built in the 1300s.

Aspiring to gallantry, the hall was named after King Arthur and decorated with paintings, tapestries, ship models, armor, coats of arms, and cages with exotic birds.

The beautiful facades of the city’s Old Town buildings resemble those of Amsterdam and Stockholm. Although most of it was rebuilt after World War II, the architecture reflects Gdańsk’s rich medieval period.

Several gems have been salvaged, including Saint Mary’s Church, built by the Teutonic Knights in the 1300s. Perched over the river is a medieval crane, the largest in Europe, capable of lifting four tons. It unloaded and repaired ships using gears, pulleys, and the power of humans inside of giant hamster wheels.

Along the Old Town’s Royal Way is a monument to Daniel Fahrenheit, inventor of the mercury thermometer. He was born just a block away in 1686. The Fahrenheit scale was the temperature standard worldwide until the 1960s when it was widely replaced by Celsius (except in the U.S.).

Baltic gem

Amber is fossilized forty-million-year-old tree sap. Almost three-fourths of the world’s supply of amber comes from northern Poland.

The organic gemstone is mined, raked from the floor of the Baltic Sea, or simply collected from the beach. Sometimes the stones contain remains of ancient animals and plants trapped in the resin.

Amber has been worn as jewelry by humans for over thirteen thousand years. Other uses include cups, bowls, chests, candelabras, chess pieces, pipes, and umbrella handles. The Amber Museum in Gdańsk displays an electric guitar made from amber.

Hard labor

After World War II, the Soviet Union used intimidation, rigged elections, and propaganda to suppress several countries formerly controlled by the Nazis. The war was over, but according to some Poles, only the occupier changed.

In Gdańsk, dissatisfaction with price increases, low wages, and food shortages led to a series of strikes and demonstrations. At a protest in 1970, soldiers and police killed forty-four picketers and wounded a thousand more.

At the time Lech Wałęsa was an electrician at the Gdańsk Shipyard and an activist in an illegal labor union. For his ongoing role in the uprisings, he was frequently harassed, surveilled, and arrested. In 1976 he was fired.

In 1980 sixty-year-old Anna Walentynowicz was also fired from the shipyard, due to her involvement in a union. The act enraged her fellow workers. They stopped work and demanded her reinstatement.

Upon news of the strike, Wałęsa climbed over the locked shipyard fence near Gate No. 2 and took charge of the initiative. The protest lasted eighteen days. Family and friends delivered food, blankets, and encouragement to the seventeen thousand protesters inside the gates.

As news spread, Wałęsa helped direct strikes at twenty other plants across Poland. The inter-factory strike committee presented a list of twenty-one demands to the government.

The demands read much like the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. They included freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to form labor unions, and the right to strike. Other demands addressed economic conditions and health care access for Polish citizens.

The twenty-one demands were neatly lettered in red and black on two sheets of plywood and fastened to Gate No. 2 for the world to see. Fearing a national revolt, the puppet government agreed to talk.

Occasionally, Wałęsa climbed onto the cab of a truck next to the gate to update the crowd outside on the status of the negotiations.

The Gdańsk Agreement was signed in August 1980. Wałęsa used a giant ballpoint pen with an image of newly elected Pope John Paul II on it. (The pope, Karol Wojtyła, was Polish.)

The agreement allowed for the creation of a national labor union called Solidarity. It was the first time a communist government legalized a union. With Wałęsa as chair, Solidarity quickly grew to ten million members, a quarter of Poland’s population.

Rising stars, falling satellites

Wałęsa’s role in the strike, the negotiations, and the newly formed union propelled him to fame internationally.

In 1981 the walrus-mustachioed electrician was Time magazine’s Person of the Year. In 1983 he won the Nobel Prize for Peace.

But the fight wasn’t over. As Solidarity grew in strength, the Soviet-backed government moved to destroy it. The union was suspended, Wałęsa and the rest of the leadership jailed, and martial law in Poland declared.

Continuing discontent with the status quo fueled wave after wave of street demonstrations and strikes. In 1988 nationwide rallies forced the government, once again, to open talks with the outlawed union.

As a result of the negotiations, the government of Poland was restructured with a president and a two-chamber legislature. An election was scheduled. Solidarity was not only legalized, but recognized as a legitimate political party.

Arrogantly, the Moscow-backed autocrats expected to maintain a majority after the election. Instead, the outcome of the voting shocked them, along with the rest of the world.

Solidarity candidates captured all of the lower-house seats for which they competed and ninety-nine out of one hundred seats in the upper house.

It was an upset beyond all expectations. An earthquake.

In 1990 Lech Wałęsa was elected as the Republic of Poland’s first president. The communist era was over.

Poland’s success at freeing itself from the control of the Soviet Union was closely watched and emulated by other satellite nations. In 1989 Hungary opened its borders, the Berlin Wall crumbled, and Czechoslovakia staged its own peaceful revolution.

More defections followed. In 1991 the Soviet Union formally dissolved, a state of affairs once unimaginable.

Yard work

Today, Gate No. 2 at the Gdańsk Shipyard is a shrine. A plywood replica of the twenty-one demands hangs at the entrance.

Outside the gate is the Monument to the Fallen of 1970. The cross-and-anchor sculpture was designed and built by shipyard workers.

The European Solidarity Museum in the heart of the shipyard is built to look like the hull of a ship.

It tells the story of the Solidarity movement with photos, film, and artifacts, such as a bullet-riddled jacket worn by a protester in 1970.

The original plywood panels with the twenty-one demands are displayed inside. The gift shop sells fake Wałęsa-style walrus mustaches.

Wałęsa has received awards and honorary degrees from dozens of countries and universities. The Gdańsk airport was renamed for him. In the U.S., he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

At the time of this writing, he is eighty years old and still living in Gdańsk. He occasionally attends services at Saint Bridget’s Church across the street from the Amber Museum.

Saint Bridget’s is a bit of an amber museum as well. Its massive altar is made entirely of the petrified resin and features sculptures of saints, Poland’s coat of arms, crosses wielded during the Solidarity strikes, and a monstrance containing relics of Pope John Paul II.

Crusading and stargazing

The tour headed south of Gdańsk through flat, fertile fields of wheat and corn. Forty percent of Poland is farmland.

We stopped to walk the grounds of Malbork Castle, one of the largest in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The fortress was built during the 1300s by the Teutonic Knights, a German Catholic religious order of warrior-monks.

During the Third Crusade in the 1000s, the knights attempted to capture Jerusalem from the Egyptians. The effort failed, so they instead resorted to crusading against non-Catholics in Europe. They converted or killed pagan Lithuanians and Orthodox Russians and stole their lands for the trouble. An alliance of Poles, Lithuanians, and others effectively decimated the cult in 1410.

In 1543 a book was published that changed the world—or at least how people thought about it. The book, On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres by Nicolaus Copernicus, presented the theory that the earth revolved around the sun, rather than the other way around.

The concept wasn’t a new one, but the astronomer was the first to present it mathematically. The introduction of the Copernican model is a major event in the history of science.

A statue of hometown boy Copernicus stands in the market square of Toruń, one of the oldest cities in Poland. Toruń’s original medieval architecture was undamaged during World War II.

In the 1300s Toruń was a member of the Hanseatic League and a major marketplace. That circumstance ensured Toruń’s bakers a ready supply of rare spices, such as ginger, cinnamon, and anise. The city is known for its gingerbread baking, a tradition for a thousand years.

I left my heart in Warsaw

Fryderyk Chopin, the composer and pianist, grew up in Warsaw. A child prodigy, he was giving public concerts by the age of seven. A few years later, he was publishing original compositions. He left Poland at the age of twenty, never to return.

Chopin settled in Paris, where he sold compositions and gave piano lessons to the aristocracy. In his life he performed publicly only thirty times. Instead, he played salons—small social gatherings of the rich and famous.

For most of his life, Chopin’s health was poor. He died in Paris in 1849 at the age of thirty-nine. On his deathbed, he asked that his heart be returned to Poland. The organ was removed and preserved in alcohol.

His sister Ludwika transported Chopin’s heart across Europe, concealed in a jar hidden beneath her clothes. She smuggled the organ past customs agents in multiple countries to its final destination—inside of a column in the Church of the Holy Cross of Warsaw.

A plaque on the column reads, “For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

Bullet holes and bees

In Warsaw, I checked into the Chopin Boutique, a former apartment building undergoing slow restoration. In 1944 the building was in the middle of fierce fighting, as it was just across the street from an underground newspaper office. Bullet holes can be seen near the entrance and around the property.

The owner of the hotel, Jarek, keeps bee hives on the roof. Their honey is available at breakfast.

The Chopin is a tall building with high ceilings, wide hallways, and grand stairwells. Music filters upstairs each night. On the second floor is a parlor, where Jarek has resurrected the ambiance of Chopin’s salon recitals. Pianists from the Chopin University of Music perform every evening.

One evening at Chopin Botique, we were served a traditional Ukrainian dinner of herring salad, borscht, cabbage rolls, and apple pie. Ukrainian folk artists played music on an accordion and bandura. They thanked us for America’s support.

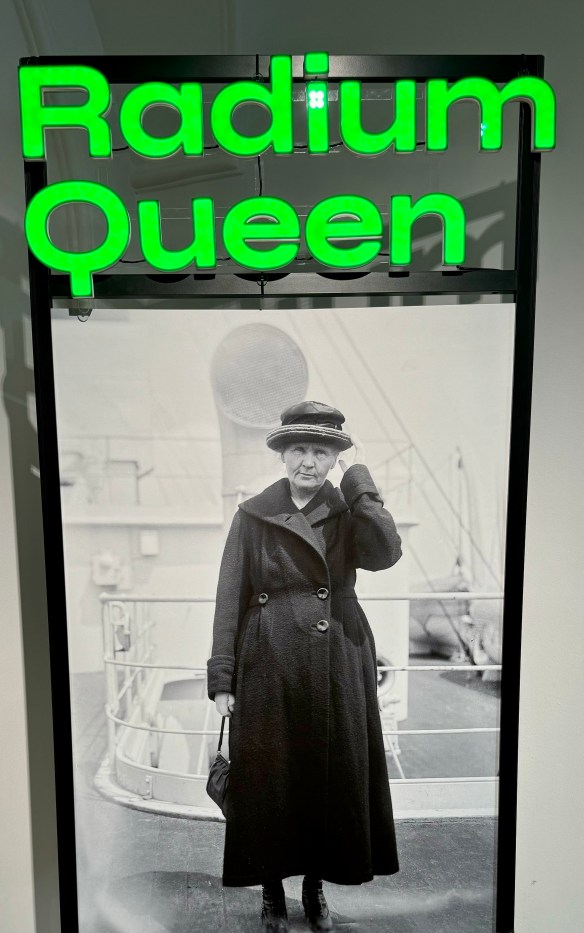

Radium queen

Maria Skłodowska (skwo DOAF ska) was born in Warsaw in 1867. She studied science on her own until, at the age of twenty-four, she moved to Paris. There, she took university-level courses in physics, chemistry, and mathematics.

Pierre Curie was an instructor at another institution. The couple met and discovered their mutual passion for science. They married and eventually collaborated. I toured the small Skłodowska-Curie Museum, located in the building in which Maria was born.

The Curie’s theories of radioactivity, a word Maria coined, earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. She was the first female prize winner. A decade later, she won another Nobel by herself, the prize for chemistry. She is the only person to win Nobel prizes in two different sciences.

Maria Curie died at the age of sixty-six from overexposure to radioactivity.

In the ghetto

In 1939, two weeks after the Nazis invaded Poland from the west, the Soviets invaded from the east. Caught in a vise, the whole of Poland was conquered and occupied in just five weeks.

In 1940 the entire Jewish population of Warsaw, some thirty percent of the city, was herded into a few walled city blocks. The Warsaw Ghetto housed over four hundred thousand Jews. Tens of thousands died of starvation, disease, and executions.

In 1941 Germany turned against its former partner-in-crime and attacked the Soviet Union. For the rest of the war, all of Poland was occupied by the Nazis. Six extermination camps were built, including Treblinka and Auschwitz. Millions of Jews were transported across occupied Europe to be murdered in the camps.

In 1942 the Warsaw Ghetto occupants were transferred en masse to the camps. When the order came to obliterate the ghetto, a few hundred Jewish fighters launched an uprising.

Despite being heavily outnumbered, the resistors held out for a month. The Nazis, to smoke out the fighters, burned the ghetto to the ground block by block. When the fighting ended, most of the survivors were killed.

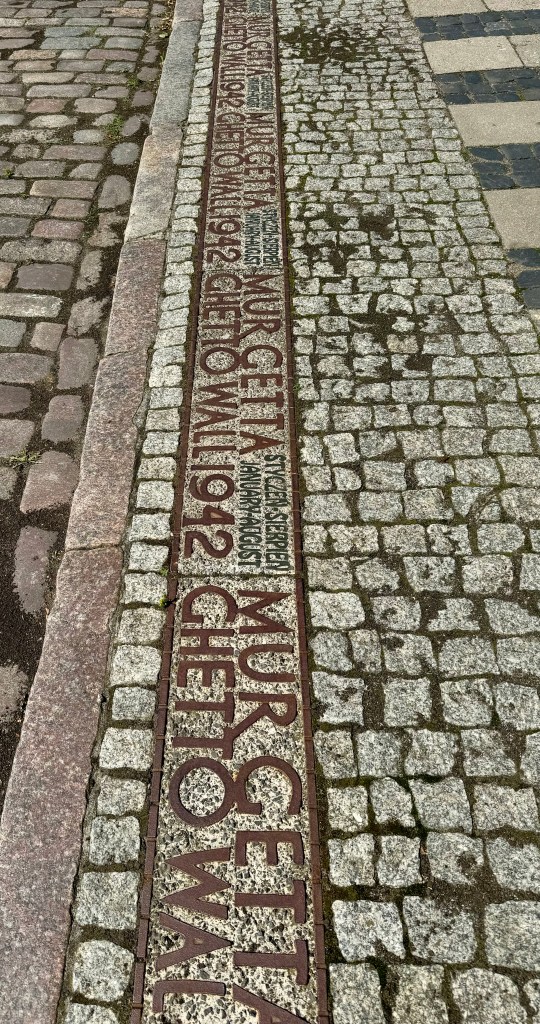

With local guide Kasia, I toured a few surviving sections of the wall, a few tenement houses, and the Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Little evidence of the ghetto is left. Paving stones in the sidewalks mark the former locations of the walls.

We stopped at the previous location of the railroad loading yard. There, during the summer of 1942, three hundred thousand people were deported to Treblinka and murdered in the gas chambers.

We visited the site of the wooden footbridge, featured in the movie The Pianist. The bridge was built to connect the two walled sections of the ghetto and to separate prisoners from the Germans and ethnic Poles passing on the thoroughfare below. (The movie’s director, Roman Polański, survived the Kraków Ghetto.)

In a small park, a grassy mound covers the Anielewicz Bunker, which served as the underground headquarters of one of the Jewish resistance groups. When the Nazis discovered the bunker, a few resistors escaped through the sewers. The rest, over a hundred fighters, committed mass suicide. The buried bunker is a tomb.

From the ashes

In 1944, the Polish government-in-exile, inspired by D-Day and sensing the imminent end of the war, ordered the Polish resistance to retake Warsaw from the Nazis. The Poles waged urban war for sixty-three days, but were forced to surrender.

The remaining fighters were transported to death camps. A furious Hitler ordered Warsaw burned to the ground. Eighty-five percent of the city was destroyed, including the historic old town and the royal castle. Over 150,000 Polish civilians were killed. In total, Warsaw lost eight hundred thousand people during World War II, eighty percent of its population.

In January 1945, Russian and Polish troops entered the ruins of Warsaw, and liberated what was left of it. Since then, the city has been completely rebuilt.

I walked the mile-long Royal Way from the statue of Charles de Gaulle to the castle. The street is crowded with cafés, bakeries, hotels, churches, and shops. The former communist party headquarters built by the Soviets recently housed, ironically, Poland’s stock exchange.

Along the way, benches play selections of Chopin’s music at the push of a button. One is located in front of the Church of the Holy Cross, where his heart is entombed.

I passed the gates of Warsaw University, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and the Presidential Palace. Everywhere, plaques and monuments commemorate victims of the war.

The art deco-style Hotel Bristol was used by the Nazis as a headquarters. More recently, scores of celebrities have been guests, including Bill Gates, Mick Jagger, Pablo Picasso, President Kennedy, Ray Charles, Dalai Lama, Queen Elizabeth, Sophia Loren, and Tina Turner.

Today, Warsaw is one of the most populous cities in the EU with 3¼ million residents.

Moving borders

After the war, the Allies redrew Poland’s borders. To punish Germany, they lopped thirty-nine thousand square miles from its eastern edge and gave them to Poland.

Then, they decided to reward Russia by handing it a sixty-nine-thousand-square-mile chunk of eastern Poland. Today, those areas are part of Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania.

As a result, some people who were born in Poland are now Ukrainian. Some who were born in Germany are now Polish. Millions of Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews were forced to migrate across the new borders.

Overall, Poland’s territory was reduced in size by fourteen percent. As local guide Marcin said, “Same country—different shape.”

In from the cold

One of the stories told in Warsaw’s Cold War Museum is that of Ryszard Kukliński, a Polish army colonel who became an American spy.

During the Soviet occupation of Poland, the Polish military answered to the Soviets. Kukliński was disturbed by their orders to take part in the invasion of Czechoslovakia and to use deadly force against Polish workers during the 1970 strikes.

He contacted a U.S. embassy and volunteered to share Soviet military secrets. Beginning in 1972, he began a long, nerve-racking assignment with the CIA, ultimately sharing thirty-five thousand pages of secret documents.

In 1981, facing looming discovery, Kukliński, his wife, and two sons were secreted out of Poland to the U.S.

In 2004 Kukliński died from a stroke at the age of seventy-three. His remains were transported to Warsaw, where he was buried with honors.

Kukliński’s code name was Jack Strong. A film about him, a tense spy thriller by the same name, was produced in Poland.

Black Madonna

On the way to Kraków, we stopped to visit the Jasna Góra Monastery and the painting of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, the most revered symbol of Polish catholicism.

The complex, a pilgrimage site for millions each year, is massive. Among the monastery’s most treasured exhibits is the 1983 Nobel prize medal, gifted by Lech Wałęsa.

The Black Madonna painting, most likely created in the 1200s, was vandalized in 1430. The slashes to Mary’s face were intentionally highlighted during its restoration.

On a daily schedule, the image is covered for a few hours behind a sliding metallic curtain and then uncovered.

We attended its unveiling. A large crowd gathered for the event. Music played. Slowly the curtain was raised. A bit of a magic trick. Now you see her, now you don’t.

Factory tour

Before traveling to Poland, I rewatched Schindler’s List to reacquaint myself with the story of the German industrialist and humanitarian.

During World War II, Oskar Schindler, a business opportunist, took over a Jewish-owned factory in Kraków that manufactured pots and pans, and later munitions. He employed hundreds of Jews who would otherwise have been transported to extermination camps.

I toured the building that once housed the factory and now is the home of the Schindler Museum. Nothing from its days as a factory remains. Before the Soviets drove the Nazis out of Poland in 1945, Schindler was forced to move the factory to Nazi-controlled Czechoslovakia. To protect his workers, he took them with him.

Some scenes from the movie were shot both inside and outside of the building. In the room that served as Schindler’s office is a monument made of enameled pots and pans, one for each of the twelve hundred Jews he saved from certain death. The monument includes a list of their names—Schindler’s list.

A former Nazi, Schindler is buried on Mount Zion in Jerusalem.

Empty chairs

Kraków dates to the 300s. Poland’s kings once called it home. The city was the capital of Poland until 1596 when the government moved to Warsaw.

Although looted by various occupiers, the city was largely undamaged at the end of World War II. Today Kraków’s population is eight hundred thousand.

A wall with forty-six towers and seven entrances used to protect Kraków. In the 1800s the walls were torn down and replaced with a park that now rings the city.

In the center of the old town is the largest medieval square in Europe. Overlooking the square is Saint Mary’s Basilica, built in the 1300s. From its tower, sentinels used to watch for fires or attacks. When trouble was spotted, a bugle was sounded.

Today, a bugler in the tower plays once every hour of the day, all year long.

The musical passage is paused in the middle in memory of a bugler who was shot in the throat while sounding the alarm about an impending attack upon the city.

The castle complex on Wawel Hill commands a view of the city and the Vistula River. It was established in the 1300s on the orders of Kazimierz the Great and enlarged over the centuries. When the Nazis were in town, they ensconced themselves within the ancient walls.

As in other Polish cities, the Jewish population of Kraków was crowded into a walled ghetto and then transferred to extermination camps. Auschwitz is nearby.

The point of transfer was Plac Zgody, a square in the center of the ghetto. Residents were required to stand in line during roll call. They were forced to leave family heirlooms and furniture behind. The square was often filled with wardrobes, cabinets, tables, and chairs. Some of the residents were executed on the spot.

The plaza, now a memorial site, has been renamed Ghetto Heroes Square. Sixty-eight empty chairs, an artistic representation of the sixty-eight thousand people deported from the square, are arranged in rows, as if standing for roll call.

Immigrant heroes

I joined a walking tour of the Wawel castle grounds, including the cathedral. Over the centuries, most Polish kings were crowned in the cathedral and many are buried there, next to saints, presidents, and poets.

One of the vaults contains the remains of a hero of the American Revolutionary War.

Tadeusz Kościuszko was a Polish military leader, but in 1776 he served as a colonel in the Continental Army. An accomplished architect, he helped design West Point.

In 1783, the Continental Congress promoted him to brigadier general. He returned to Poland to fight against Russia.

Another Revolutionary War hero is Kazimierz Pułaski, also a Polish military leader who became a general in the Continental Army. Benjamin Franklin met Pułaski in Europe and recommended him to George Washington.

Pułaski established and led the army’s first cavalry regiment. While leading a charge against the British, he was wounded and died shortly thereafter.

Pierogi school

At the hotel we were divided into teams of four or five. A chef was assigned to each team. Ours was Kasia. She walked us to a market, Stary Kleparz, the oldest in Kraków, operating since 1367.

Kasia gave us a list of ingredients in Polish and taught us to pronounce them phonetically. Then we visited vendor after vendor, trying out our language skills while gathering food.

I said dzień dobry (hello) before I ordered kapusty kizoney (sauerkraut) and ogórki kiszonej (pickles). Others ordered kielbasa, eggs, cheese, and sour cream.

With groceries in hand, we took an Uber to Kasia’s studio apartment in the suburbs. There, we mixed and kneaded dough for pierogi. While the dough rested, we made a filling of mashed potatoes, sautéed onions, and cheese. The dough was rolled into a thin layer and circles were cookie-cut with the edge of a glass.

We placed a dollop of filling on each circle of dough, folded it in half, and crimped the edges to form a dumpling. When the pierogi rose to the surface of boiling water, we ladled them out and promptly devoured them.

“Don’t worry about cleaning your plate in Poland,” Agnes advised us. “If you clean it, here comes babcia (grandmother) with more pierogi.”

After reading this I feel like I just had a lovely tour of Poland. I sure hope all of your writings are going into a beautifully bound book. Good to know you are still traveling, learning and sharing your stories.

Thanks Kirk. Great article. Brings back memories of my Polish buddies from Cleveland and their moms’ pierogis.

sds

Nicely done, Kirk. My mom was born in Łódź, but I’ve never been. Thanks for sharing your adventures. I feel like I was right there with you.

Thanks, Kirk. This brought back a million memories. Back in my grad school days I studied German lit and my favorite author was Gunter Grass. He was born in Gdansk when it was part of Germany and so writes in German. He has great passion for Poland and its history. One of the themes in his novel, “The Tin Drum” is “Poland is lost. Poland is not lost. Poland is not yet lost.” It reflects the capacity of the Poles for hope in Poland’s future. That novel contains a very moving scene in the Gdansk post office during the siege.

I’m a Chicago boy of mixed Polish/German ancestry. My grandmother was born in Myszienc, a very small town in NE Poland, at the end of the 19th century. She immigrated to the States after WWI. We visited that town about 15 years ago, met relatives, and had dinner in her childhood home. From there we traveled to Gdansk, Malbork Castle, Częstochowa, Warsaw and Cracow, an itinerary very similar to yours. It was a fabulous trip.

Thanks for your comments, Art. I became aware of “The Tin Drum” during the trip and have added it to my reading list.

I always enjoy traveling with you, Kirk. I learn so much each time. I see you’re going to my favorite city, Prague, this fall. Make sure you spend time in the Jewish Quarter.