Three historic trails lead to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

One arrives from Mexico City—El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (the Royal Road of the Interior Land). For centuries, Native North Americans used the sixteen-hundred-mile trade route.

In 1598 Spanish settlers first followed El Camino Real north. It was traveled continuously until 1882.

Another trail enters Santa Fe from the west. Approximately seven hundred miles long, the Old Spanish Trail connected Santa Fe with settlements in California. Blazed as early as the 1500s, the Old Spanish Trail was used by Native Americans, explorers, trappers, and traders until 1848.

A third route, the namesake Santa Fe Trail, connected Santa Fe with the eastern United States, specifically Franklin, Missouri. The nine-hundred-mile trail was established in 1821 to take advantage of new trade opportunities with Mexico, which had just broken away from Spain. It saw use until around 1880.

Three American cultures intersected at the crossroads of Santa Fe—Native, Hispanic, and Anglo. It seemed an appropriate trail’s end for my tour as well.

Ruler for a day

The Spanish established the area along the Santa Fe River in 1610 as La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís (the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi). Or Santa Fe, for short.

The town became the capital of the Spanish province of Nuevo México and, as such, is the oldest capital and the second-oldest city in the United States. (Consider that the Pilgrims didn’t arrive at Plymouth Rock until ten years later.)

The rulers of Santa Fe and the surrounding territory played musical chairs. In 1680, Native Americans drove the Spanish out and occupied the town. In 1692, the Spanish won it back, then lost it to Mexico when Mexico won its independence in 1810.

In 1848, the United States gained the New Mexico Territory through a treaty. During the Civil War, Confederate troops occupied the town for a few days until the arrival of the Union army.

The influences of Native Americans, conquistadors, fur trappers, cowboys, and artists are apparent everywhere.

Once a drab, squat town (“the Siberia of the Mexican Republic”), Santa Fe now attracts celebrities, writers, artists, musicians, hikers, skiers, Mexican immigrants, retirees, tourists, and new-age hippies.

I checked into monastic Hotel Saint Francis, Santa Fe’s oldest hotel. In the historic plaza I sat on a park bench to warm myself in the sun. A dog trotted by wearing sunglasses. A busker played a violin on the spot where stagecoach passengers once disembarked. School kids ate their lunches near where Billy the Kid was held in chains.

And Native Americans gathered, as they have for centuries, to sell handmade crafts under the portico of the Palace of the Governors, the oldest continuously occupied public building in the United States.

War zone

In 1878, Lewis Wallace, a Union general, was named governor of the New Mexico Territory. The timing of his appointment put him on a collision course with Billy the Kid.

Wallace arrived in Santa Fe in the middle of a deadly war between two political factions in prosperous Lincoln County.

Each side, led by prominent businessmen, recruited strange-bedfellow gangs of lawmen and criminals for protection.

One gang, the Regulators, counted William H. Bonney, also known as Billy the Kid, as a member. Despite the Kid’s eventual notoriety, he never robbed a bank, train, or stagecoach. He scraped by as a small-time cattle rustler until his sharpshooting propelled him into history.

Sheriff William Brady, sent to arrest the Kid and the other Regulators for a series of revenge murders, was himself killed in a shoot-out. A few weeks later, 150 members of the two gangs faced off in the town of Lincoln. After five days of shooting, twenty-two were killed and twenty-three wounded.

When Governor Wallace arrived at his post, he ordered the arrest of the Kid and the Regulators.

No kidding

The Kid wrote to the governor several times, promising to surrender and testify in a related murder trial in exchange for dropped charges.

During a secret meeting, Wallace assured the Kid that, as an informant, he would receive a full pardon.

The Kid turned himself in and testified as agreed, but the local DA revoked Wallace’s bargain and refused to set the Kid free. Instead, he was charged with the murder of Sheriff Brady.

The judge, when sentencing, told the Kid he was going to hang until he was “dead, dead, dead.” According to a questionable legend, the Kid responded, “You can go to hell, hell, hell.”

Again, the Kid escaped and, while on the lam, killed more men. He is known to have taken at least nine lives before his own death at the hands of Sheriff Pat Garrett. He was twenty-one-years-old.

A bronze plaque on the Cornell Building commemorates the site of the jail that held the Kid before the trial. In the New Mexico History Museum his spurs are on display.

Throughout the conflict, Governor Wallace spent his evenings in the Palace of the Governors, dodging bullets and working on his novel, Ben-Hur: A Tale Of The Christ, published in 1880. Ben-Hur was the best-selling novel of the 1800s and the basis for an Academy Award-winning movie.

Coneheads

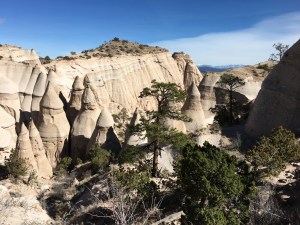

The next day dawned sunny—perfect for hiking with the hoodoos.

I drove one hour west of town to Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument, passing two flocks of Sandhill cranes grazing nonchalantly in the fields like cattle.

Cochiti Pueblo and the Bureau of Land Management have “concurrent jurisdiction” over Kasha-Katuwe (white cliffs). Getting to the trailhead requires driving through a few miles of well-fenced tribal land after registering at a pueblo-staffed ranger station.

I hiked both available pathways in the park. The Slot Canyon Trail leads between white pumice walls only a few inches wide in some places. I slid through sideways. The high, sheer cliff faces sliced the blue sky into a narrow wedge over my head. In places, rock piles blocked the slot and scrambling was necessary to continue.

Along the way I found petroglyphs carved into the side of a cliff. Most prominent was the wavy-bodied figure of a snake, approximately five feet long.

Archaeologists have found evidence of human habitation in the area from four thousand years ago. When Coronado, the Spanish conquistador, barged through in 1540, Cochiti Pueblo was well established. Today’s puebloans are its descendants.

Further along the trail, the canyon widens and reveals a cluster of the namesake tent rocks. The tapered formations vary in height up to nine stories high. They look like giant traffic cones or the points of sharpened pencils.

I have overused the descriptions surreal and otherworldly in my reporting, but they certainly apply to the tent rocks.

The formations were caused by a volcanic eruption millions of years ago. The explosion deposited layers of ash, which eventually eroded leaving behind canyons and pinnacles. The hoodoos, made of soft pumice and tuff, are topped with harder, precariously perched caprocks. Some have lost their caps.

After a six-hundred-foot climb to a mesa, I was rewarded with a view over valleys bristling with tent rocks, resembling clusters of bottle rockets. I returned though the canyon and embarked on the shorter Cave Trail, which features more hoodoos and a small cave carved into the side of a cliff.

Holes in the wall

Ten thousand years ago, humans lived in Frijoles Canyon, forty minutes northwest of Santa Fe.

The remains of more recent homes, dating between 1150 and 1550 CE, still crowd the canyon, which is now within Bandelier National Monument.

The ancient inhabitants carved homes into the soft canyon walls and planted corn, beans, and squash on the mesas above. They hunted squirrels, rabbits, and deer, and raised turkeys.

I walked the trail through the canyon, which provides access to scores of stone ruins as well as petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings).

Along the creek, the remains of a three-story structure with over four hundred rooms was arranged in a circle around a courtyard. Hundreds lived side by side in the Ytuonyi Peublo in what amounted to an ancient apartment complex.

Nearby is an excavated kiva, a forty-feet-wide circular underground room used by the community for meetings and ceremonies.

The park’s trail veers to the base of the cliffs, which are composed of tuff, a soft rock made of compressed volcanic ash.

Tuff is naturally riddled with holes, like swiss cheese, which have provided shelter for both people and animals. Some of the openings were enlarged by the puebloans to create cavates (rooms) with round doors and windows.

Hundreds of homes have been gouged from the cliffs. I climbed up the wooden ladders and stepped inside a few of them. The ceilings are still blackened from ancient cook fires. Other rooms were built against the cliff walls for support. Some were once as tall as four stories. Holes for their roof beams are visible in the walls.

Hundreds more carved rooms peer down from the canyon walls. As tempting as they are to explore, they are inaccessible. Off-trail hiking is not permitted.

The path continued in the shade back and forth across the creek to Alcove House. To see the reconstructed kiva within the high alcove requires a 140-foot climb up multiple stairways and four ladders.

By 1550, the Frijoles Canyon puebloans had moved to the area adjoining Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument. During World War II the monument was closed and its buildings used to house the developers of the atomic bomb at nearby Los Alamos.

I continued driving deeper into the Jemez Mountains, a steep uphill grade through snow, evergreens, and tree stumps charred from forest fires.

Finally, I reached Valle Grande, a grass valley within Valles Caldera National Preserve. Valles Caldera is a fourteen-mile-wide volcanic crater, containing hot springs, fumaroles, and lava domes. A million years ago the Jemez eruption was six hundred times more powerful than the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens.

Low Road

Overnight, an inch or two of snow frosted the desert scrub. I headed northeast. The Low Road from Santa Fe to Taos passes through seventy miles of the Rio Grande Gorge with the river flowing on the left and the twelve-thousand-foot Sangre de Cristo range emerging on the horizon.

When the Spanish arrived to “found” Taos in 1615, a pueblo had already been in place for centuries. Taos and Acoma pueblos have been continuously occupied for over a thousand years and are considered to be the oldest continuously inhabited communities in the United States.

Some portions of Taos Pueblo are five stories high. About 150 puebloans live in the adobe building year-round. Electricity and indoor plumbing are prohibited. Taos Pueblo is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In the late 1800s, the scenery and climate of the area attracted an art colony, which remains vibrant today. Writers, such as D.H. Lawrence, Aldous Huxley, and Carl Jung, found inspiration in Taos. Scenes from Easy Rider were shot nearby. The population is a laid-back mix of artists, hippies, Native Americans, and descendants of Spanish settlers.

Antihero

I visited the adobe home of Kit Carson, now a museum. Carson was a famed mountain man, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and US Army officer. Although illiterate, he could speak eleven Native American languages and was a skilled negotiator.

Carson became a legend in his own lifetime due to exaggerated versions of his exploits in dime novels.

While not all of the stories are true, no historian disputes his bravery or his impact on the history of the West. He is either a hero or a villain, depending upon one’s perspective.

The tour started with a film about Carson’s life, produced by the History Channel. The role of Carson was played by his great-great-grandson, who bears a remarkable resemblance.

Carson left Missouri at age sixteen to become a fur trapper. He married first into the Arapaho tribe and, later, the Cheyenne tribe. In the 1840s, Carson achieved national fame (unbeknownst to him) through the exaggerated storytelling of fellow explorer, John Fremont.

In 1849, while attempting to rescue some settlers taken hostage by the Apache, Carson stumbled upon a book of tall tales about himself.

The novel, of which he had no prior knowledge, portrayed him as a larger-than-life hero. Carson had the book read to him and was disgusted by its exaggerations.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some historians portrayed Carson as a genocidal killer of thousands of Native Americans. Many puebloans still consider him a butcher.

More recently, perspectives have shifted somewhat, as Carson has been given partial credit for a late change of heart. He was disheartened by his own role in driving the Navajo from their homeland and petitioned Congress to allow them to return. As a US Indian agent, he earned a reputation among Native Americans for treating them honestly and fairly.

Carson purchased a four-room adobe house in Taos in 1843 for his third wife, a Mexican American. They lived there until 1866 with their six children. They are buried together in the nearby Kit Carson Memorial Cemetery.

High Road

From Taos I took the High Road back to Santa Fe. The road winds through the forested slopes, broad mesas, and rocky ridges of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Pecos Wilderness, Santa Fe National Forest, and Carson National Forest.

The elevation ranges to over thirteen thousand feet, much of it forested with spruce, pine, and fir.

Tucked along the way are tiny Spanish land-grant villages and Native American pueblos. Many are now remote artists’ enclaves.

I stopped for delicious chicken stew and homemade bread at Sugar Nymphs Bistro in Peñasco. In Las Trampas, a village founded in 1751, I visited the San José de Gracia Church, completed in 1776, the same year the Declaration of Independence was signed. It is considered a model of Spanish colonial architecture and is a National Historic Landmark.

The village of Truchas is on a high mesa, a scattering of run-down adobe houses on dusty unpaved alleys, backed by the snowcapped Truchas Peaks. Many weavers, painters, and jewelry makers maintain studios and galleries in town.

The road descended into a fertile valley and the town of Chimayó, where I visited the Santuario de Chimayó, another National Historic Landmark.

Built between 1811 and 1816, this tiny adobe church is visited by over three hundred thousand pilgrims each year. It has been called by some the most important Catholic pilgrimage site in the United States.

Inside, a round pit in the center of a small room contains “holy dirt,” believed to have healing powers. An adjacent prayer room displays milagros, votive candles, photographs, rosary beads, and dozens of discarded crutches.

The area around the church has been expanded to offer amenities to pilgrims (and tourists), including a park, art galleries, souvenir shops, and restaurants. The descendants of Chimayó’s original Spanish settlers maintain several traditional weaving studios.

A foot for a foot

In nearby Española, I passed the bronze equestrian statue of Juan de Oñate y Salazar, erected in 1991 at the Oñate Monument Visitors Center. Oñate, a conquistador, led early expeditions into the Southwest and founded numerous settlements.

Along the way, he gained a reputation among the Native Americans for brutality.

In 1598, his men demanded supplies from the Acoma Pueblo, reserves which were needed by the tribe to survive the coming winter. The ensuing skirmish resulted in the death of several Spaniards, including Oñate’s nephew.

A year later, Oñate retaliated in a strike that killed hundreds of Acoma. He enslaved the survivors. Most cruelly, he rounded up twenty-four male puebloans over the age of twenty-five and amputated their right feet.

Oñate went on to serve as governor of Spanish New Mexico.

On a night in 1998, a Native American commando group sneaked into the grounds of the visitor center in Española and left a note: “We see no glory in celebrating Oñate’s fourth centennial, and we do not want our faces rubbed in it.”

Then, with an electric saw, they severed the statue’s right foot.

So, have you purchased a “pueblo” yet for your vacations? Sounds like you might do well in Taos, which looked pretty empty to me when we were last there. But it was Spring and they say that many places don’t open until at least a month later . . . i.e., late May or June.

Bruce

Thanks, Kirk. This is one of my favorite parts of the US. Glad you made it up to Bandelier and Valle Grande. In all my visits I’ve never made it to Tent Rocks. Next time for sure.

As always, very enjoyable reading. It brought back lots of happy memories.