For the Allies, capturing the French port of Cherbourg in the northwestern corner of Normandy was a top priority.

The invasion force needed a deep-water harbor from which to readily unload troops, equipment, and supplies for its push onto the continent. Early control of Cherbourg was critical to Operation Overlord’s success.

Hitler believed any Allied invasion would fail without Cherbourg and ordered the city to be made invincible.

Over the centuries the city and port, surrounded by cliffs, had been fortified many times. The Nazis bolstered the historical battlements with a nine-mile perimeter of forts and pillboxes, mortar and machine-gun emplacements, tunnels, minefields, anti-tank ditches, and barbed wire.

Twenty artillery batteries were installed. Twenty-one thousand defenders were dug in.

Twelve days after D-Day the Allies launched their attack on Cherbourg. Meanwhile, the Germans began to demolish the port’s facilities and mine the harbor.

Allied progress through the barriers was slow and the fighting furious. In support of the ground troops, United States Navy ships bombarded the city. Finally, at the end of June, Cherbourg was captured, but at a high cost. Twenty-eight hundred Americans gave their lives to take the port. Over thirteen thousand more were wounded. Thousands of German troops surrendered.

Most of the mines were swept from the harbor by mid-July. Six weeks after D-Day and two weeks after the capture of Cherbourg, transport ships from England began to arrive.

My dad was aboard one of them. He was barely eighteen.

Bastard/Conqueror

In the 800s, after the Celts, Romans, Saxons, and Bretons took turns settling the northern coast of what is now France, the Vikings invaded. The name Normandy reflects the origin of those conquerors. Norsemen or Northmen became Normans.

A couple of hundred years later and across the channel, England was ruled by the aging Edward the Confessor. Edward was celibate and had no successors. When he died in 1006, many laid claim to his throne. One was Harold, Edward’s brother-in-law; another was William, Edward’s cousin.

The legend is that Harold promised to support William’s claim, but then, upon Edward’s death, broke his promise and claimed the throne of England for himself. Harold was the first king to be coronated in Westminster Abbey.

William (also known as William the Bastard, presumably for reasons of legitimacy and not personality) rallied his Norman army and crossed the channel into southern England.

After a fourteen-hour battle against Harold’s Anglo-Saxon forces, William, now known as Smokey the Bear, I mean William the Conqueror, was victorious.

King Harold was killed in the Battle of Hastings. William seized the crown and became the first Norman king of England.

Nine hundred years later, the Allies crossed the same English Channel from the opposite direction and conquered Nazi-occupied Normandy.

Comic strip

The story of William, Harold, and the Norman Conquest is told in a nine-hundred-year-old graphic novel of sorts. With vibrant embroidered images and few words, the Bayeux Tapestry reveals ambition, betrayal, and conquest.

The tale is told not with ink, but with yarn. Not with pen strokes, but with stitches. Not on paper, but on linen. The tapestry is seventy-five yards long and just nineteen inches tall, featuring fifty-eight explicit scenes of royal intrigue and war, right down to the decapitated heads.

In 1077 the embroidery was presented to William as a birthday gift, draped around the inside of the Bayeux Cathedral.

History is written by the survivors, which are usually the victors. In this case, history was stitched by the conquerors to justify the Norman conquest of England. Several movies have featured images from the tapestry in opening and closing credits.

Viewing the tapestry requires horizontal scrolling, or rather strolling, as it is displayed full-length in the Bayeux Tapestry Museum.

Cider and cheese

Normandy is slightly larger than Massachusetts and has a population of 3½ million. Its coastline features long stretches of beach interspersed with steep cliffs.

When the Allies reached Normandy’s interior in 1944, they found rolling green hills crisscrossed with hedgerows and marshy river channels. Navigating it while under fire took longer than planned.

In the 1800s impressionist painters flocked to the region for its landscapes and light. Artists drawn to Normandy include Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, Paul Gauguin, George Seurat, and Pablo Picasso.

The area is still primarily agricultural, a land of dairy farms, horse pastures, and apple orchards. Local cuisine includes mussels, Camembert cheese, and hard apple cider.

Skull and bones

I walked from Rouen’s train station to the hotel in a downpour. While I stood dripping wet in from of the desk clerk, she tried to hide her amusement at my soppy appearance.

After changing into dry clothes, I headed out to explore.

Rouen was once one of the largest and richest cities in Europe. A port on the River Seine, Rouen has two thousand half-timbered buildings, about one hundred of which date from before 1520.

To get my bearings, I walked the length of Rue du Gros Horloge (Street of the Big Clock) and many of its side streets. The clock dates from the 1300s.

So does the Plague Cemetery, a mass grave for the internment of bodies during the Great Plague.

Approximately three-fourths of the parish were killed by the Black Death. During a later plague in the 1500s, four wings of half-timbered and stone houses were built around the cemetery to serve as bone depositories. The Ossuary of Saint-Maclou is decorated with skulls, bones, and gravediggers’ tools.

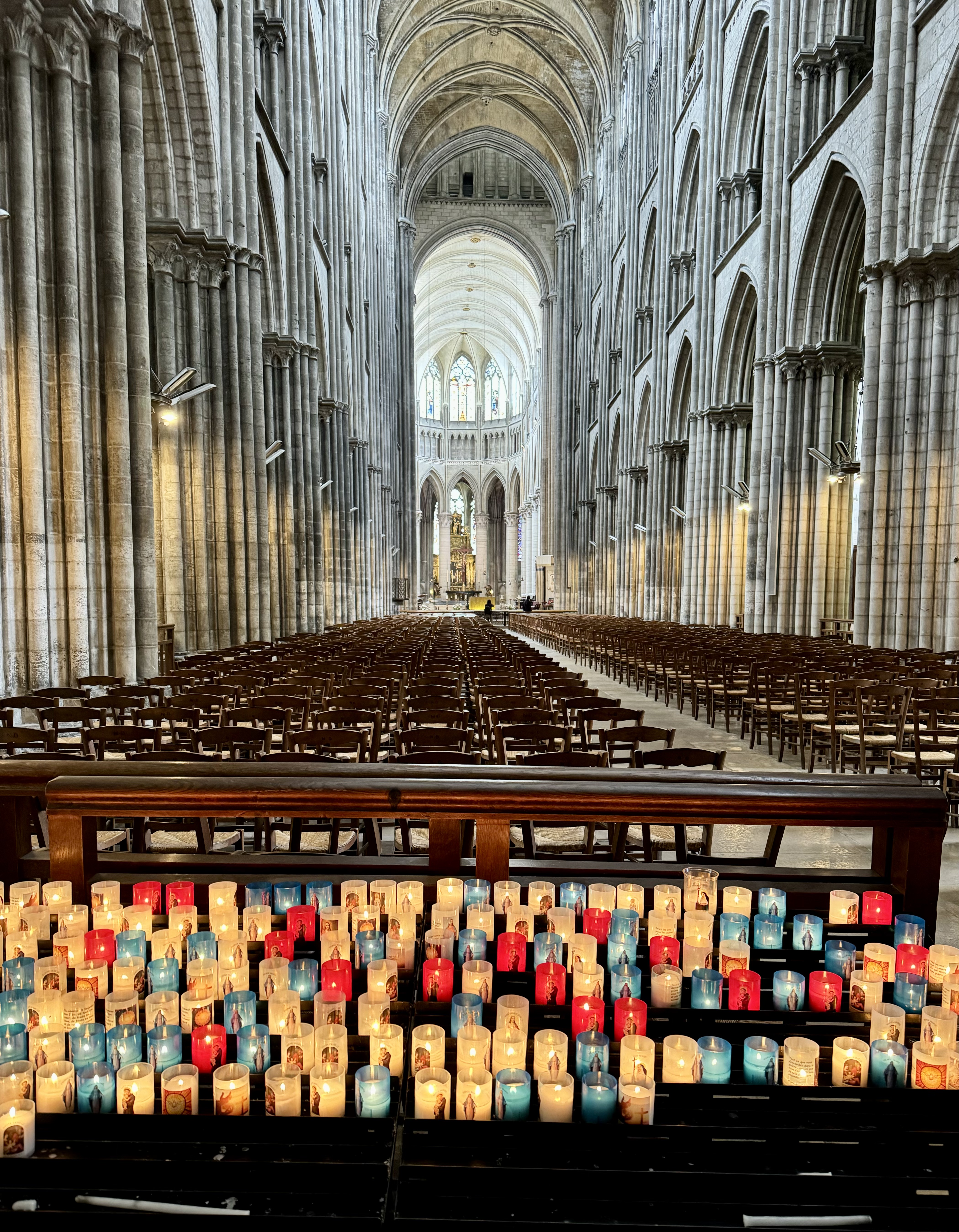

My hotel room faced the Rouen Cathedral. Built and rebuilt over a period of more than eight hundred years, the cathedral was once the tallest building in the world. Each of the cathedral’s three towers boasts a different architectural style.

Charlemagne visited an earlier version of the church in 769. William the Bastard-soon-to-be-Conqueror was present during the cathedral’s 1063 consecration. A tomb inside may contain the heart of King Richard the Lionheart.

The cathedral was a favorite subject of impressionist Claude Monet. He painted the west facade dozens of times, experimenting with different lighting and weather conditions. One of his easel positions is marked on the sidewalk.

Julia

Founded in 1345, La Couronne is the oldest restaurant in France. While attending a luncheon there in 1948, American Julia Child had a revelation. “It was the most exiting meal of my life,” she said. The meal inspired her to dedicate her life to teaching French cooking.

During World War II, Julia McWilliams worked as a researcher for an intelligence agency. In 1946, she married Paul Child, another researcher. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. State Department appointed Paul to a post in France and the couple moved to Paris.

Following her epiphany in Rouen, Julia enrolled in a cooking course at Le Cordon Bleu. Upon graduation, she and two classmates collaborated on the book Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

The book, a best seller, launched Child’s career. In the 1970s and 1980s, she starred in numerous television cooking shows, through which she introduced Americans to French cuisine.

. . . And Joan

Across the street from La Couronne is another landmark—a tall cross marks the spot in Rouen’s old marketplace where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in 1431.

Throughout her short life, Joan claimed to be guided by the voices of saints.

During France’s Hundred Years’ War with England, those voices instructed her to seek an audience with Charles VII, king of the part of France unconquered by England.

At the time, a prophecy was circulating in France that a young girl would arise and lead France’s army to victory. Joan claimed to be that young girl.

In 1429 Charles agreed to meet with her. Convinced of her passion and divine inspiration, he sent her to Orléans, a city under siege, to see what she could do.

In just nine days, she rallied the French troops to fight and drove the English army away from the gates.

With Joan’s cheerleading, the French regained the initiative. They pursued the English, retook lost territory, and recaptured Reims, the city where French kings were historically crowned. At the insistence of Joan, Charles marched to Reims and was coronated in its cathedral, continuing the royal tradition.

A year later, Joan was captured by the English and imprisoned. In a mock trial, she was declared guilty and executed. She was nineteen years old.

In France, Joan of Arc is regarded as a freedom fighter, a symbol of the country’s independence, and an early feminist. The Roman Catholic Church declared her a saint.

Sheet shows

In Le Havre I stepped into the bus station and bought a ticket to Honfleur. A crowd queued to board, but there was some problem. The ticket scanner on the bus wasn’t approving most of the tickets. Maybe the scanner was malfunctioning; maybe the tickets were issued incorrectly. Boarding was bottlenecked.

The driver spoke only French, but many of the passengers didn’t. Finally the driver ignored the tickets and waved everyone on board. The bus was hot; the aisle was crowded with luggage. Two cyclists showed up late, delaying the start. They attached their bikes to the rear of the bus and lugged all of their camping gear inside.

I asked the girl across the aisle if she knew what the issue was. She laughed and said, “Eet eez a sheet show.”

Picturesque Honfleur is located across the River Seine from Le Havre. In the mid-1100s, the town was a major seaport. In the 1600s, Honfleur traded with Canada, the Caribbean, and Africa. It was one of France’s primary slave ports.

Tall skinny houses with slate-covered fronts surround the old port on three sides. World War II did little damage.

I ate a seafood galette for lunch in a snug crêperie overlooking the water. Entering required stepping carefully over two ancient German boxers asleep in the doorway.

Crêpes and galettes are favorites in northern France. Crêpes are sweet and eaten as a dessert. They are made with wheat flour.

Crispy-edged galettes are savory and eaten as a main. Made with buckwheat flour, galettes often feature ham, veggies, or cheese. Single sunny-side-up eggs may sprawl on top.

Uphill is Sainte-Catherine’s Church, overlooking the harbor. Dating to the 1400s, Sainte-Catherine’s is the largest wooden church in France. It was constructed by descendants of Vikings using axes, not saws. The nave looks like an upside-down ship’s hull.

I walked along the river to the mouth of the Seine and a view of the Normandy Bridge. A sailboat motored into the lock, rammed the side, backed up, broke a warning sign on the other side, and finally backed out. The lockkeeper laughed. Another sheet show.

Jack, Sam, and Bob

While touring the coast, I found monuments to three French explorers who starred in my grade-school history books.

Jacques Cartier was born in Saint-Malo in 1491. On his first voyage to North America, he explored the coast of Newfoundland and the Saint Lawrence River. While poking around, he heard Native Americans use the word kanata, meaning settlement. By 1545, European maps were denoting the region as Canada. A statue of Cartier is on the ramparts at Saint-Malo and his remains are buried inside the cathedral.

In Honfleur I found a plaque dedicated to Samuel de Champlain, an explorer and mapmaker born in the town. In 1603, Champlain led his first journey to Canada, exploring the Saint Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. During an expedition in 1608, he founded Quebec City, where his native tongue is still spoken.

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (known to most as La Salle) was born in Rouen in 1643. La Salle was an explorer and fur trader in North America. In 1682 he canoed down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico and claimed the area for France. He named it La Louisiane (Louisiana) after King Louis XIV.

Island in the tide

Next day, I traveled by bus and train past thatched cottages, stone manor houses, horse farms, and hedgerows to Mont-Saint-Michel.

I had seen photos of the famous medieval monastery perched on its stack of rock, but I wasn’t prepared for how fantastical it appears in person. It seems to rise from the sea and hover above the horizon like a mirage. Like the Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz.

The island is half of a mile offshore across a broad mud flat. The tide rises by as much as fifty feet and recedes eight miles from the shore. At low tide the abbey is accessible to religious pilgrims who have been visiting from all over Europe since the Middle Ages. High tide is capable of stranding or drowning the unwary.

A river, which serves as a border between the regions of Normandy and Brittany, used to meander from one side of the island to the other. The two regions fought over control of the mount. A dam built in 2010 settled the issue by defining the river’s course—Mont-Saint-Michel is now permanently in Normandy.

Hermits sought isolation on the island as early as the 500s. In 708 a religious sanctuary was built on the cliff top. The Bayeux Tapestry features an image of Harold (soon-to-be king of England) rescuing two Norman knights from quicksand in the flats in 1065.

During World War II, German soldiers used Mont-Saint-Michel as an aircraft-tracking station and lookout post. On August 1, 1944, a single American soldier, Private Freeman Brougher, two British reporters, and a mob of excited villagers liberated Mont-Saint-Michel. The few remaining Germans surrendered.

A bridge to the island was built in 2015, replacing a causeway. A bus deposited me more than halfway across and I walked the rest of the way. Already, dozens of morning strollers were squishing their way through the muck around the island.

I crossed through the two gates and began climbing the one and only street on the island, a narrow and steep cobbled lane to the abbey. For centuries, the Grand Rue was lined with mediocre inns and tacky souvenir shops catering to visitors. Nothing has changed.

The abbey is a multi-story engineering marvel, a maze of grand halls and steep stone stairwells clinging to a pyramid of solid granite. On top is the church, cloisters, and a refectory. Beneath them are huge crypts containing work rooms and quarters for monks and nuns. Fishers and farmers used to live in the village at the base of the abbey walls.

The day-trippers clear the mount by late afternoon. Including the monks and nuns, only a few dozen people live on the island. In the evening I toured the ramparts. The view is expansive with Brittany to the west and Normandy to the east.

Along the Grand Rue, a gathering of trad musicians, Bretons likely, played Celtic music on accordions, while people danced in the street.

Saving Breizh

The Breton Peninsula juts into the Atlantic Ocean and accounts for a third of the coastline of France. Humans settled in Brittany around thirty-five thousand years ago. Brittany is the site of some of the world’s oldest and largest standing stones.

Bretons, the inhabitants of Brittany (Breizh), are proud of being one of the six Celtic nations, which include Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and the Isle of Man. Brittany was an independent kingdom until 1532.

The Breton language is not officially recognized by France. Until the late 1960s, public schools attempted to eradicate it. Giving children Breton names and playing Celtic music was outlawed prior to 1993.

In the early 2000s only two hundred thousand Bretons could speak their traditional language. Most of them were over sixty. Breton is classified as “severely endangered” by UNESCO.

More recently, a small percentage of children have begun attending bilingual classes.

The population of Brittany is five hundred thousand, most of whom are fishers or farmers. Brittany provides the France with most of its seafood and vegetables. A nationalist movement seeks independence from France.

All the mall we can see

After reading All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, I was anticipating an authentic Breton experience inside the walls of Saint-Malo.

The town is the main setting in the 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel and was a filming location for the TV series.

Saint-Malo began as a monastery in the 500s. (Malo was a Welsh monk.) In the 1500s the town declared itself an independent republic.

The port was notorious for a couple of centuries as a friendly haven for both French privateers and pirates. (Privateers steal for you; pirates steal from you.) These royally endorsed robbers enriched the city (and France) at the expense of England, Holland, and Spain.

During World War II, the town was almost completely destroyed by Allied bombing.

Saint-Malo was reconstructed during the 1950s and reimagined, not as a quaint village, but as an upscale retail mall and beach resort. Shopping, sunbathing, and rampart-strolling are the main activities.

Fifteen miles upriver from Saint-Malo is the town of Dinan and a more expected Breton experience. In 1077 the town was referenced on the Bayou Tapestry: “Here the knights of Duke William fight against the men of Dinan.” During the Middle Ages, Dinan’s merchants and guild members traded with England and Holland. The port bustled with weavers and tanners.

To protect their wealth, the merchants built their homes on the bluff overlooking the river. A fortified wall was erected in the 1200s. Today, cafés and a bakery selling kouign amann (butter cake) surround a medieval bridge.

From the port I walked up the steep cobblestone Rue du Petit Fort, through the gate, and into the old town. There, I found half-timbered houses, crêperies, a clock tower built in the 1400s, and shops selling tins of locally caught sardines, mackerel, and tuna.

A cry and a warning

Before arriving in France, I toured Poland (Please see “Same country, different shape.”) and, while I was there, the Auschwitz extermination camp.

Today, Auschwitz is both a museum and a memorial. As grim as I knew the visit would be, I felt an obligation to the victims to honor their existence and acknowledge the horror.

One hundred and fifty buildings remain. Guided tours visit a few of the barracks, which house exhibits on how the victims were processed, lived (briefly), and were murdered.

Heartbreaking artifacts are on display, including piles of collected personal items—tens of thousands of pairs of shoes, thousands of suitcases, forty-thousand pairs of eyeglasses. One room is filled with hundreds of prosthetics.

Some of the barracks include memorials honoring the victims of individual countries, such as Anne Frank from the Netherlands. She and her sister passed through Auschwitz on the way to Bergen-Bergen, where they died a few months later. Their mother died at Auschwitz.

The walking tour visits the gas chamber, crematorium, and gallows, where the camp commander was hanged after his eventual trial and conviction.

Nearby is phase two of the camp, Birkenau. Its railroad tracks run past the imposing guard tower to the dividing platform, where life-and-death decisions were made in seconds. The tour visited more barracks and the remains of gas chambers and crematoria.

Beyond its role as a museum, Auschwitz is also a memorial to the millions who passed under the Arbeit Macht Frei sign and never left.

Of the 1.3 million people transported to the camp, 1.1 million were murdered.

The victims include one million Jews, seventy-five thousand Poles, twenty-one thousand Romani, fifteen thousand Soviet POWs, and up to fifteen thousand others.

Those not gassed died via starvation, disease, executions, or medical experiments. At peak efficiency, the camp murdered ten thousand people per day, most within twenty-four hours of arrival.

On the grounds at Birkenau is the International Monument to the Victims of Fascism. The plaque reads, in part, “Forever let this place be a cry of despair and a warning to humanity . . .”

The story of Auschwitz is difficult to process. It makes no sense. And yet it happened. I can’t grasp the monstrosity of it. I can’t find the words. I left the camp sickened, depressed, and angry.

The largest mass murder in a single location in history occurred at Auschwitz. Why not bulldoze the place?

Because the mission of the museum is to “further a deeper understanding of the origins of intolerance, racism, and anti-Semitism” and “foster reflection about the meaning of personal responsibility.”

“Especially,” the guide added, “given the existence of Holocaust deniers.”

Remains of the day

Visiting Auschwitz heightened my interest in touring the D-Day sites of Normandy.

News of the mass murders in occupied Europe leaked to the Allies in 1942, but the scale of the atrocities was likely not known until the death camps were liberated following D-Day.

“It’s hard to imagine what the consequences would have been had the Allies lost,” said the deputy director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library. “You could make the argument that they saved the world.”

I stayed in Bayeux, a Norman town near the memorials, museums, and remnants of the invasion.

Just six miles from the coast, Bayeux was the first town to be liberated by the Allies. Its infrastructure was largely untouched by the war.

Signs in the shop windows welcomed visitors to the eightieth anniversary of the invasion, celebrated a week before my visit.

Approximately 150 American veterans attended, a few of whom fought on D-Day. The youngest was ninety-six.

Most of the Americans in the first wave to reach Omaha Beach were exhausted from lack of sleep, soaked from the waves, seasick, and scared.

Upon landing, they slogged through water and sand, while carrying a hundred pounds of gear and dodging bullets.

The shore was studded with obstacles and mines, and crisscrossed by rifle and mortar fire. Eleven machine-gun nests aimed at them from the cliffs.

It was a killing pit. More than two thousand U.S troops died or were wounded while taking control of the four-mile-long beach. Nearly half of all D-Day casualties were suffered on Omaha.

On the day of my visit, Omaha looked like any other beach. The sky was sunny, waves lapped the shore, birds careened in the breeze. Being there, where so much blood was spilled, felt surreal.

A monument at Pointe du Hoc honors the Army Rangers who scaled one-hundred-foot cliffs while under fire, in order to dismantle the massive gun battery on top. The cliffs were heavily bombed by the Allies, pocking the top with craters.

Once they grappled up the cliff face, the Rangers overcame resistance from German troops only to discover the guns had been moved a half of a mile inland. Once found, they were quickly destroyed. Remnants of the six gun placements, bunkers, and trenches remain on the bluff among the craters.

When paratrooper John Steele jumped into Normandy the night before D-Day, his chute snagged on the roof of a church in the village of Sainte-Mère-Église. Helplessly, he hung above the square for two hours until he was captured. Today, the story is “reenacted” by a uniformed mannequin dangling from the church’s pinnacle. (Steele survived World War II.)

While in the village, I visited the Airborne Museum, dedicated to the thirteen thousand paratroopers and four thousand glider infantrymen who dropped into Normandy before dawn.

At Utah Beach is a life-size replica of a landing boat. The originals were flat-bottomed, had plywood sides, and held thirty-six soldiers each. Near the village of Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, I stopped at the Leadership Monument, featuring a statue of Major Richard Winters. His story is told in the Band of Brothers TV series.

Bipartisan aid

Overnight, Robert Wright and Ken Moore landed by parachute near the tiny village of Angoville-au-Plain. They didn’t know each other. Both were combat medics. They decided to set up a field hospital in the rural Church of Saint Côme and Saint Damien. They hung a red-cross banner outside the entrance.

While the fighting raged around them, they gathered and arranged wounded men in the pews. At one point a mortar shell fell through the roof. Fortunately, it did not detonate. Wright tossed it out of a window.

By the end of the day, about eighty men, both Americans and Germans, were under their care. An American officer entered the church and announced that German forces had broken through the American defenses. He suggested they retreat. Wright and Moore decided to stay with the wounded.

Soon after, a German officer arrived. When he noticed that wounded German soldiers were being treated as well as Allies, he agreed to respect the aid station’s neutrality.

Today, blood stains are still visible on the church pews. Stained-glass windows honor the 101st Airborne Division.

A monument to the two medics stands outside of the church. Wright’s ashes are buried in its graveyard. He is from Columbus, Ohio.

Finally, I visited the American Cemetery on a peaceful bluff above the beaches. There, the remains of over nine thousand American military dead are buried beneath bright white marble crosses and stars. On the Wall of the Missing (MIA) are the names of over fifteen hundred.

Of the 156,000 Allied troops who landed on Normandy’s beaches, approximately nine thousand were casualties on June 6.

By the end of the campaign for Normandy, the Allies suffered more than two hundred thousand casualties, including over fifty thousand killed.

By the end of August, 1944, the Germans had been pushed out of northwestern France and Paris had been liberated. The Battle of Normandy was over.

Dad and De Gaulle

I was just a few miles from Cherbourg, where my dad had arrived in mid-July, 1944, two weeks after the city’s liberation.

When they handed him ammunition, he became understandably anxious.

“We were told there were still snipers,” he said in his memoir. “We got a pep talk on why we were here and what we must do. We were prepared to load our rifles and start shooting.

“We were revved up and ready for anything,” he said. “But we were not prepared for . . . Red Cross personnel, mostly women, handing us a cup of coffee and a donut as we left the ship. What a comedown!”

Dad was a petty officer in the U.S. Navy, and assigned to a unit that evaluated, photographed, and forwarded captured military documents. He was quartered in a rowhouse on the waterfront. “There was much damage to the city and quite a few destroyed vehicles scattered about.”

“We saw German prisoners of war helping to rebuild railroad tracks. Later, we saw carloads of prisoners . . . unloaded to board ships . . .” The Germans were headed to POW camps in the U.S. and Canada.

“The thing that bothered me was the number of men, women, and children begging for any food left on our trays,” he said. “Some of us started taking more than we wanted so we could pass the food to hungry people.”

On August 20, 1944, General Charles de Gaulle, chair of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, spoke from the balcony of Cherbourg’s city hall.

“There was a huge crowd and I wanted to get close enough to take a picture,” Dad said. “I told the MP I was an official U.S. Navy photographer, which I was, but not assigned to photograph this event. He let me through the roped-off area and I got a couple of close shots of General De Gaulle.”

In late 1944, Dad was reassigned to London, where he celebrated VE Day (May 8, 1945) and VJ Day (August 14, 1945) before returning to the States.

“When I got home, there was no one there,” he said. “So I decided to shave and clean up. Just as I finished shaving, I heard the car in the drive. I went to the door, but Mama and Daddy didn’t get out of the car. They had picked up their mail and were sitting there reading it.

“I couldn’t wait any longer, so I opened the door and ran out to the car. They were really surprised. The letter I sent about two weeks before telling them I was coming home arrived the same day I did. That was the letter they were reading.”

Excellent!

I appreciate you continuing to share your travels. It’s fun to learn history from you!